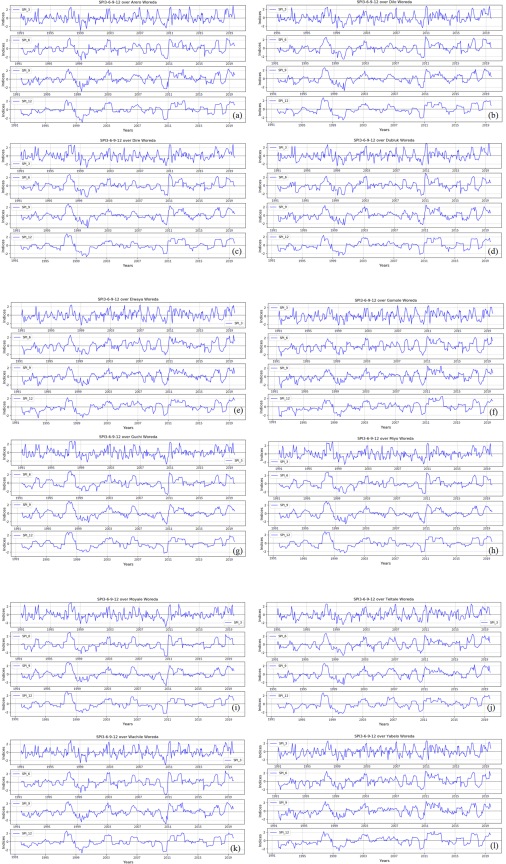

Drought is one of the most frequent natural disasters in the world, droughts has a significantly negative impact on social, economic, and environmental situations. The goal is to assess and define the spatiotemporal analysis of meteorological droughts across ENSO (neutral, El Niño and La Niña) events and provided the guidance of the study area. CHIRPS data gathered from CHG-UCSB for spatial analysis and USGS FEWS NET for temporal analysis, respectively, for the time periods 1981 2020 and 1991–2020. For spatial and temporal analysis SPI was selected due to better for rainfall input over the study area, we employed Python tools and GeoCLIM data analysis methodologies. The findings of this study demonstrate that the Borana zone experienced an increase in droughts during the El Niño, La Niña, and neutral events between 1981 and 2020. The frequency and duration of the dryness were displayed in time steps across short-term drought indices. The extent, duration, and frequency of meteorological (deficit of precipitation) droughts varied, as shown by the time-scale temporal meteorological drought indices in the range of three to twelve months. For the remaining woredas of investigation between the SPI3 and SPI6, SPI6 and SPI12, and SPI9 and SPI12 indices, significantly an increase in the correlation values over short to long durations over the study area was the dominant factor in the meteorological drought severity of the correlation. It is also necessary to conduct additional research on how droughts spread, including the use of various drought indices to gauge the frequency, length, and intensity of droughts over time at the woreda, regional, and national levels. This study will help for different sectors, for knowledge’s and references to better manage irrigation, crop variety selection (drought tolerant seeds), soil conservation, crop production, and better awareness on meteorological droughts over study area.

| Published in | American Journal of Remote Sensing (Volume 12, Issue 2) |

| DOI | 10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13 |

| Page(s) | 53-70 |

| Creative Commons |

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. |

| Copyright |

Copyright © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Science Publishing Group |

Spatial Analysis, Meteorological Drought, ENSO, SPI, Impact

No. | SPI Value | Drought Severity Class |

|---|---|---|

1 | 2.0 and above | No drought |

2 | 1.5 to 1.99 | No drought |

3 | to 1.49 | No drought |

4 | 0.99 to -0.99 | Slight drought |

5 | -1.0 to -1.99 | Moderate drought |

6 | -1.5 to -1.99 | Severe drought |

7 | -2.0 and less | Very severe drought |

Cross-correlation for Woredas | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Arero | Dilo | |||||||

Cross-correlation | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 |

SPI_3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

SPI_6 | 0.6661 | 1 | 0.7070 | 1 | ||||

SPI_9 | 0.5320 | 0.7961 | 1 | 0.6187 | 0.8464 | 1 | ||

SPI_12 | 0.4786 | 0.6855 | 0.8403 | 1 | 0.5463 | 0.7591 | 0.8909 | 1 |

Dire | Dubluk | |||||||

Cross-correlation | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 |

SPI_3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

SPI_6 | 0.6997 | 1 | 0.6626 | 1 | ||||

SPI_9 | 0.6183 | 0.8510 | 1 | 0.5354 | 0.7831 | 1 | ||

SPI_12 | 0.5644 | 0.7663 | 0.8939 | 1 | 0.4480 | 0.6595 | 0.8369 | 1 |

Elwaya | Gomole | |||||||

Cross-correlation | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 |

SPI_3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

SPI_6 | 0.7126 | 1 | 0.6694 | 1 | ||||

SPI_9 | 0.5792 | 0.8192 | 1 | 0.5059 | 0.7783 | 1 | ||

SPI_12 | 0.4859 | 0.7027 | 0.8504 | 1 | 0.4136 | 0.6372 | 0.8094 | 1 |

Guchi | Miyo | |||||||

Cross-correlation | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 |

SPI_3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

SPI_6 | 0.7079 | 1 | 0.7062 | 1 | ||||

SPI_9 | 0.6239 | 0.8625 | 1 | 0.6236 | 0.8623 | 1 | ||

SPI_12 | 0.5838 | 0.7814 | 0.8999 | 1 | 0.5778 | 0.7779 | 0.8994 | 1 |

Moyale | Teltale | |||||||

Cross-correlation | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 |

SPI_3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

SPI_6 | 0.7079 | 1 | 0.7382 | 1 | ||||

SPI_9 | 0.6058 | 0.8499 | 1 | 0.6374 | 0.8494 | 1 | ||

SPI_12 | 0.5731 | 0.7614 | 0.8919 | 1 | 0.5495 | 0.7599 | 0.8865 | 1 |

Wachile | Yabelo | |||||||

Cross-correlation | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 | SPI3 | SPI6 | SPI9 | SPI12 |

SPI_3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

SPI_6 | 0.6754 | 1 | 0.6631 | 1 | ||||

SPI_9 | 0.5616 | 0.8177 | 1 | 0.5189 | 0.7792 | 1 | ||

SPI_12 | 0.5169 | 0.7231 | 0.8644 | 1 | 0.4195 | 0.6440 | 0.8146 | 1 |

CHIRPS | Climate Hazards Group Infra-Red Precipitation with Stations |

ENSO | El-Niño-Southern Oscillation |

FEWS NET | Famine Early Warning Systems Network |

SNNPR | South Nations and Nationalities Peoples’ Region |

SPI | Standardized Precipitation Index |

USGS | United State Geological Survey |

| [1] | Gebrechorkos, S. H., Peng, J., Dyer, E., Miralles, D. G., Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Funk, C., Beck, H. E., Asfaw, D. T., Singer, M. B., & Dadson, S. J. (2023). Global High-Resolution Drought Indices for 1981–2022. Earth System Science Data Discussions, 2023, 1–28. |

| [2] | Sanogo, A., Owusu, P. A., Kabange, R. S., Djire, B. I., Donkoh, R. F., & Dia, N. (2023). Meteorological Drought Detection and Forecast Using Standardized Precipitation Index and Univariate Distribution Models: Case Study of Bamako, Mali. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 11(7), 30–55. |

| [3] | Omar, A. A., Chiang, J.-L., & Daud, B. H. (2023). Spatiotemporal Analysis of Meteorological Drought Using Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) in Gabiley Region, Somaliland. Journal of Geoscience and Environment Protection, 11(5), 47–59. |

| [4] | Sharma, A. P. M., Jhajharia, D., Yurembam, G. S., Gupta, S., Patle, G. T., & Chanu, T. L. (2023). Spatiotemporal Analysis of Meteorological Drought in Tripura. In Integrated Drought Management, Volume 2 (pp. 57–70). CRC Press. |

| [5] | Serrano, S. M. V., El Kenawy, A., Zabalza-Martínez, J., Noguera, I., Peña-Angulo, D., Juez, C., Franquesa, M., Fernández-Duque, B., Domínguez-Castro, F., & Eklundh, L. (2023). Influence of the interannual variability of meteorological drought on the cross-interactions of ecological and hydrological drought in the central Spanish Pyrenees. GeoFocus. International Review of Geographical Information Science and Technology, 31, 55–85. |

| [6] | Tp, H. (2023). Economic impact of drought on agrarian society: The case study of a village in Maharashtra, India. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 103912. |

| [7] | Nazneen, S., Ayaz, T., Durrani, Y., Ali, N., Habib, M., & Yousaf, S. (2023). Meteorological Drought Measurement with Deficit in Rainfall Occurrence According to SPI Indices: a case Study of Peshawar, Pakistan. Arid Ecosystems, 13(1), 20–28. |

| [8] | Pandey, V., Pandey, P. K., & Lalrammawii, H. P. (2023). Characterization and return period analysis of meteorological drought under the humid subtropical climate of Manipur, northeast India. Natural Hazards Research. |

| [9] | Yu, H., Wang, L., Zhang, J., & Chen, Y. (2023). A global drought-aridity index: The spatiotemporal standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. Ecological Indicators, 153, 110484. |

| [10] | Zhang, M., Yang, X., Pan, M., Zhang, L., Fang, X., & Sheffield, J. (2023). Spatio-temporal characteristics and driving factors of the meteorological drought across China based on CMIP6. Hydrology Research, 54(3), 382–400. |

| [11] | Thi, N. Q., Govind, A., Le, M.-H., Linh, N. T., Anh, T. T. M., Hai, N. K., & Ha, T. V. (2023). Spatiotemporal characterization of droughts and vegetation response in Northwest Africa from 1981 to 2020. The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 26(3), 393–401. |

| [12] | Mahto, S. S., & Mishra, V. (2023). Increasing risk of simultaneous occurrence of flash drought in major global croplands. Environmental Research Letters, 18(4), 44044. |

| [13] | LIANG, J., HU, Z., & XIE, Z. (2023). Exogenous melatonin alleviates the physiological effects of drought stress in sweet sorghum seedlings. Acta Prataculturae Sinica, 32(7), 206. |

| [14] | Abi Wijaya Angga Prahatma, W. P. (2023). Drought Analysis Using Standardized Precipitation Index (SPI) Based on Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) in Bantul and Gunung Kidul Regencies, DI Yogyakarta. Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Smart and Innovative Agriculture (ICoSIA 2022), 29, 424. |

| [15] | Angon, P. B., Mondal, S., Akter, S., Sakil, M. A., & Jalil, M. A. (2023). Roles of CRISPR to mitigate drought and salinity stresses on plants. Plant Stress, 100169. |

| [16] | Bhukya, S., Tiwari, M. K., & Patel, G. R. (2023). Assessment of Spatiotemporal Variation of Agricultural and Meteorological Drought in Gujarat (India) Using Remote Sensing and GIS. Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing, 1–18. |

| [17] | Cárdenas, O. L. (2023). Predictive association between meteorological drought and climate indices in the state of Sinaloa, northwestern Mexico. Arabian Journal of Geosciences, 16(1), 79. |

| [18] | Elbeltagi, A., Pande, C. B., Kumar, M., Tolche, A. D., Singh, S. K., Kumar, A., & Vishwakarma, D. K. (2023). Prediction of meteorological drought and standardized precipitation index based on the random forest (RF), random tree (RT), and Gaussian process regression (GPR) models. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(15), 43183–43202. |

| [19] | Eze, E., Girma, A., Zenebe, A., Okolo, C. C., Kourouma, J. M., & Negash, E. (2022). Predictors of drought-induced crop yield/losses in two agroecologies of southern Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. Scientific Reports, 12(1), 1–14. |

| [20] | Kourouma, J. M., Eze, E., Kelem, G., Negash, E., Phiri, D., Vinya, R., Girma, A., & Zenebe, A. (2022). Spatiotemporal climate variability and meteorological drought characterization in Ethiopia. Geomatics, Natural Hazards and Risk, 13(1), 2049–2085. |

| [21] | Liou, Y.-A., & Mulualem, G. M. (2019). Spatio–temporal assessment of drought in Ethiopia and the impact of recent intense droughts. Remote Sensing, 11(15), 1828. |

| [22] | Degefu, M. A., Rowell, D. P., & Bewket, W. (2017). Teleconnections between Ethiopian rainfall variability and global SSTs: observations and methods for model evaluation. Meteorology and Atmospheric Physics, 129, 173–186. |

| [23] | Funk, C., Michaelsen, J., & Marshall, M. T. (2012). Mapping recent decadal climate variations in precipitation and temperature across eastern Africa. Remote Sensing of Drought: Innovative Monitoring Approaches, 331(7), 331–355. |

| [24] | Zeleke, T. T., Giorgi, F., Diro, G. T., & Zaitchik, B. F. (2017). Trend and periodicity of drought over Ethiopia. International Journal of Climatology, 37(13), 4733–4748. |

| [25] | Huang, S., Zhang, X., Chen, N., Li, B., Ma, H., Xu, L., Li, R., & Niyogi, D. (2021). Drought propagation modification after the construction of the Three Gorges Dam in the Yangtze River Basin. Journal of Hydrology, 603, 127138. |

| [26] | Wossenyeleh, B. K., Kasa, A. S., Verbeiren, B., & Huysmans, M. (2022). Drought propagation in the hydrological cycle in a semiarid region: a case study in the Bilate catchment, Ethiopia. Hydrogeology Journal, 30(3), 751–766. |

| [27] | Shiru, M. S., Shahid, S., Dewan, A., Chung, E.-S., Alias, N., Ahmed, K., & Hassan, Q. K. (2020). Projection of meteorological droughts in Nigeria during growing seasons under climate change scenarios. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–18. |

| [28] | Dufera, J. A., Yate, T. A., & Kenea, T. T. (2023). Spatiotemporal analysis of drought in Oromia regional state of Ethiopia over the period 1989 to 2019. Natural Hazards, 1–41. |

| [29] | Hailesilassie, W. T., Ayenew, T., & Tekleab, S. (2023). A comparative study of drought characteristics using meteorological drought indices over the central main Ethiopian Rift. Hydrology Research, 54(3), 313–329. |

| [30] | Kebede, A., Kang, M. S., & Bekele, E. (2019). Advances in mechanisms of drought tolerance in crops, with emphasis on barley. Advances in Agronomy, 156, 265–314. |

| [31] | Moloro, T. L. (2018). Spatio-temporal analysis of rainfall variability and meteorological drought: a case study in Bilate River Basin, Southern Rift Valley, Ethiopia. International Journal of Environmental Sciences & Natural Resources, 14(4), 76–89. |

| [32] | Nasir, J., Assefa, E., Zeleke, T., & Gidey, E. (2021). Meteorological Drought in Northwestern Escarpment of Ethiopian Rift Valley: detection seasonal and spatial trends. Environmental Systems Research, 10, 1–20. |

| [33] | Riché B, Hachileka E, Awuor CB, Hammill A (2009) Climate-related vulnerability and adaptive-capacity in Ethiopia’s Borana and Somali communities. International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) report. |

| [34] | Debela N, McNeil D, Bridle K, Mohammed C (2019) Adaptation to climate change in the pastoral and agro pastoral systems of Borana, South Ethiopia: options and barriers. Am J Clim Chang 8: 40–60. |

| [35] | Korecha D, Barnston AG (2007) Predictability of June to September rainfall in Ethiopia. J Am Meteorol Soc. https://doi.org/10.1175/MWR33 04.1 |

| [36] | NMA (2007) Initial National Communication of Ethiopia to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). National Meteorological Agency, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. |

| [37] | Gemedo-Dalle MBL, Isselstein J (2006) Rangeland condition and trend in the semiarid Borana lowlands, southern Oromia, Ethiopia. Afr J Range Forage Sci 23: 49–58. |

| [38] | Lasage R, Seifu A, Hoogland M, de Vries A (2010) Report on general characteristics of the Borana zone, Ethiopia. IVM Institute for Environmental Studies. VU University, Amsterdam. |

| [39] | McKee, T. B., Doesken, N. J., & Kleist, J. (1993). The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, 17(22), 179–183. |

| [40] | Gao, F., Zhang, Y., Ren, X., Yao, Y., Hao, Z., & Cai, W. (2018). Evaluation of CHIRPS and its application for drought monitoring over the Haihe River Basin, China. Natural Hazards, 92, 155–172. |

| [41] | Shen, Z., Yong, B., Gourley, J. J., Qi, W., Lu, D., Liu, J., Ren, L., Hong, Y., & Zhang, J. (2020). Recent global performance of the Climate Hazards group Infrared Precipitation (CHIRP) with Stations (CHIRPS). Journal of Hydrology, 591, 125284. |

| [42] | Abramowitz, M., & Stegun, I. A. (1965). Handbook of mathematical functions Dover Publications. New York, 361. |

| [43] | Tsakiris, G., & Vangelis, H. (2004). Towards a drought watch system based on spatial SPI. Water Resources Management, 18, 1–12. |

| [44] | Asfaw, A., Simane, B., Hassen, A., & Bantider, A. (2018). Variability and time series trend analysis of rainfall and temperature in northcentral Ethiopia: A case study in Woleka sub-basin. Weather and Climate Extremes, 19, 29–41. |

| [45] | Hill, R. V., & Porter, C. (2017). Vulnerability to drought and food price shocks: evidence from Ethiopia. World Development, 96, 65–77. |

| [46] | Gemeda, D. O. (2019). Climate change variability analysis in and around Jinka, southern Ethiopia. With special emphasis on temperature and rainfall. |

| [47] | Hundera, H., Mpandeli, S., & Bantider, A. (2019). Smallholder farmers’ awareness and perceptions of climate change in Adama district, central rift valley of Ethiopia. Weather and Climate Extremes, 26, 100230. |

| [48] | Tesfamariam B, Gessese B, Melgani F (2019) Characterizing the spatiotemporal distribution of meteorological drought as a response to climate variability: the case of rift valley lakes basin of Ethiopia. Weather Climate Extremes 26: 100237. |

| [49] | Wedajo, G. K., Muleta, M. K., Gessesse, B., & Koriche, S. A. (2019). Spatiotemporal climate and vegetation greenness changes and their nexus for Dhidhessa River Basin, Ethiopia. Environmental Systems Research, 8, 1–24. |

| [50] | Cheung, W. H., Senay, G. B., & Singh, A. (2008). Trends and spatial distribution of annual and seasonal rainfall in Ethiopia. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 28(13), 1723–1734. |

| [51] | Degefie, D. T., Seid, J., Gessesse, B., & Bedada, T. B. (2019). Agricultural drought projection in Ethiopia from 1981 to 2050: Using coordinated regional climate downscaling experiment climate data for Africa. In Extreme hydrology and climate variability (pp. 311–323). Elsevier. |

| [52] | Eshetu, G., Johansson, T. P., Garedew, W., & Yisahak, T. (2018). Climate variability and small-scale farmer adaptation strategy in setema-Gatira area of Jimmaa, southwestern Ethiopia. American Journal of Biological and Environmental Statistics. |

| [53] | Gebrechorkos, S. H., Hülsmann, S., & Bernhofer, C. (2019). Long-term trends in rainfall and temperature using high-resolution climate datasets in East Africa. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 11376. |

| [54] | Omondi, P. A., Awange, J. L., Forootan, E., Ogallo, L. A., Barakiza, R., Girmaw, G. B., Fesseha, I., Kululetera, V., Kilembe, C., & Mbati, M. M. (2014). Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes over the Greater Horn of Africa region from 1961 to 2010. International Journal of Climatology, 34(4), 1262–1277. |

| [55] | Assefa, D., & Mengistu, M. (2021). Time Series Trend and Variability Analysis of Temperature and Rainfall in West Shewa Zone of Oromia, Ethiopia. |

| [56] | Fazzini, M., Bisci, C., & Billi, P. (2015). The climate of Ethiopia. Landscapes and Landforms of Ethiopia, 65–87. |

| [57] | Ofgeha, G. Y., & Abshire, M. W. (2021). Spatio-temporal variability and trends in rainfall and temperature in anger watershed, Southwestern ethiopia. Journal of Applied Geospatial Information, 5(1), 462–472. |

| [58] | Regassa, S., Givey, C., & Castillo, G. (2010). The rain doesn’t come on time anymore: Poverty, vulnerability, and climate variability in Ethiopia. |

| [59] | Addaney, M., Jarbandhan, D. B., & Dumenu, W. K. (2023). Climate Change in Africa: Adaptation, Resilience, and Policy Innovations. Springer Nature. |

| [60] | Burka, A., Biazin, B., & Bewket, W. (2023). Drought characterization using different indices, theory of run and trend analysis in bilate river watershed, rift valley of Ethiopia. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1098113. |

| [61] | Mekonnen, E. N., Liou, Y.-A., Damene, S., Gebremariam, E., & Mulualem, G. M. (2023). Geospatial-based climate variability analysis, in Central Ethiopia Rift Valley. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 152(1–2), 151–165. |

| [62] | Jimma, T. B., Demissie, T., Diro, G. T., Ture, K., Terefe, T., & Solomon, D. (2023). Spatiotemporal variability of soil moisture over Ethiopia and its teleconnections with remote and local drivers. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 151(3–4), 1911–1929. |

| [63] | Marelign, A., & Gashu, G. (2023). analysis of Observed and Perceived climate change and Variability in gondar Zuria Woreda, northwestern ethiopia. Ethiopian Renaissance Journal of Social Sciences and the Humanities, 10(1), 61–80. |

| [64] | Shiferaw, H., Girma, A., Hadush, K., Mariam, H. G., Yazew, E., & Zenebe, A. (2023). Long-term hydroclimatic variability over the semi-arid Ethiopian highlands in relation to ENSO and IOD teleconnection signals. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 1–19. |

| [65] | Tamene, H., Ayal, D. Y., Zeleke, T. T., & Ture, K. (2023). Determinants of the choice of adaptation strategies to climate variability and extremes among pastoralist and agro-pastoralist households in Yabello and Arero Districts, Southeast Ethiopia. Climate Services, 30, 100381. |

| [66] | Tofu, D. A., & Mengistu, M. (2023). Observed time series trend analysis of climate variability and smallholder adoption of new agricultural technologies in west Shewa, Ethiopia. Scientific African, 19, e01448. |

| [67] | Aktürk, G., Çıtakoğlu, H., & Demir, V. (2023). Regional Frequency Analysis of Drought Indexes by L-Moments Method. |

| [68] | KARTAL, V. (2023). Drought Assessment of Siirt using SPI and SPEI. International Conference on Recent Academic Studies, 1(1), 11–17. |

| [69] | Muse, N. M., Tayfur, G., & Safari, M. J. S. (2023). Meteorological Drought Assessment and Trend Analysis in Puntland Region of Somalia. Sustainability, 15(13), 10652. |

| [70] | Wubneh, M. A., Alemu, M. G., Fekadie, F. T., Worku, T. A., Demamu, M. T., & Aman, T. F. (2023). Meteorological and hydrological drought monitoring and trend analysis for selected gauged watersheds in the Lake Tana basin, Ethiopia: Under future climate change impact scenario. Scientific African, 20, e01738. |

| [71] | Sara P, Wekesa M (2008) Improving drought response in pastoral areas of Ethiopia Somali and Afar Regions and Borana Zone of Oromiya Region. Humanitarian Policy Group. |

| [72] | Birhanu Z, Ambelu A, Berhanu N, Tesfaye A, Woldemichael K (2017) Understanding resilience dimensions and adaptive strategies to the impact of recurrent droughts in Borana Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia: a grounded theory approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerp h1402 0118 |

| [73] | Getahun, Y. S., & Li, M.-H. (2023). Flash drought evaluation using evaporative stress and evaporative demand drought indices: a case study from Awash River Basin (ARB), Ethiopia. Theoretical and Applied Climatology, 1–20. |

| [74] | Lambe, B. T., & Kundapura, S. (2023). Recent Changes in Hydrometeorological Extremes in the Bilate River Basin of Rift Valley, Ethiopia. Journal of Hydrologic Engineering, 28(7), 5023014. |

| [75] | Edossa DC, Babel MS, Gupta AD (2010) Drought analysis in the Awash river basin Ethiopia. Water Resour Manag. 24: 1441–1460. |

| [76] | Gebrehiwot T, van der Veena A, Maathuis B (2011) Spatial and temporal assessment of drought in the Northern highlands of Ethiopia. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf. 13: 309–321 |

| [77] | Viste E, Korecha D, Sorteberg A (2013) Recent drought and precipitation tendencies in Ethiopia. Theor Appl Climatol 112: 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1 007/s00704-012-0746-3 |

| [78] | Degefu MA, Bewket W (2014) Trends and spatial patterns of drought incidence in the omo ghibe river basin, Ethiopia. Geografiska Annaler A Phys Geogr. |

| [79] | Gizachew, Shimelis (2014) Analysis and mapping of climate change risk and vulnerability in central rift valley of Ethiopia. Afr Crop Sci J 22(Issue Supplement s4): 807–818. |

| [80] | Muluneh A, Biazin B, Stroosnijder L, Bewket W, Keesstra S (2014) Impact of predicted changes in precipitation and atmospheric carbondioxide on maize and wheat yields in the central rift Valleyof Ethiopia. Reg Environ Chang 15(6): 1105–1119. |

| [81] | Mohammed Y, Yimer F, Tadesse M, Tesfaye K (2017) Meteorological drought assessment in north east highlands of Ethiopia. Int J Climate Change Strateg Manage 10(1): 142–160. |

APA Style

Tullu, G. M., Habtegebriel, A. K., Agboka, K. M. (2024). Impact of ENSO on Drought in Borena Zone, Ethiopia. American Journal of Remote Sensing, 12(2), 53-70. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13

ACS Style

Tullu, G. M.; Habtegebriel, A. K.; Agboka, K. M. Impact of ENSO on Drought in Borena Zone, Ethiopia. Am. J. Remote Sens. 2024, 12(2), 53-70. doi: 10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13

AMA Style

Tullu GM, Habtegebriel AK, Agboka KM. Impact of ENSO on Drought in Borena Zone, Ethiopia. Am J Remote Sens. 2024;12(2):53-70. doi: 10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13

@article{10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13,

author = {Gezahegn Mergia Tullu and Abebe Kebede Habtegebriel and Komi Mensah Agboka},

title = {Impact of ENSO on Drought in Borena Zone, Ethiopia

},

journal = {American Journal of Remote Sensing},

volume = {12},

number = {2},

pages = {53-70},

doi = {10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13},

url = {https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13},

eprint = {https://article.sciencepublishinggroup.com/pdf/10.11648.j.ajrs.20241202.13},

abstract = {Drought is one of the most frequent natural disasters in the world, droughts has a significantly negative impact on social, economic, and environmental situations. The goal is to assess and define the spatiotemporal analysis of meteorological droughts across ENSO (neutral, El Niño and La Niña) events and provided the guidance of the study area. CHIRPS data gathered from CHG-UCSB for spatial analysis and USGS FEWS NET for temporal analysis, respectively, for the time periods 1981 2020 and 1991–2020. For spatial and temporal analysis SPI was selected due to better for rainfall input over the study area, we employed Python tools and GeoCLIM data analysis methodologies. The findings of this study demonstrate that the Borana zone experienced an increase in droughts during the El Niño, La Niña, and neutral events between 1981 and 2020. The frequency and duration of the dryness were displayed in time steps across short-term drought indices. The extent, duration, and frequency of meteorological (deficit of precipitation) droughts varied, as shown by the time-scale temporal meteorological drought indices in the range of three to twelve months. For the remaining woredas of investigation between the SPI3 and SPI6, SPI6 and SPI12, and SPI9 and SPI12 indices, significantly an increase in the correlation values over short to long durations over the study area was the dominant factor in the meteorological drought severity of the correlation. It is also necessary to conduct additional research on how droughts spread, including the use of various drought indices to gauge the frequency, length, and intensity of droughts over time at the woreda, regional, and national levels. This study will help for different sectors, for knowledge’s and references to better manage irrigation, crop variety selection (drought tolerant seeds), soil conservation, crop production, and better awareness on meteorological droughts over study area.

},

year = {2024}

}

TY - JOUR T1 - Impact of ENSO on Drought in Borena Zone, Ethiopia AU - Gezahegn Mergia Tullu AU - Abebe Kebede Habtegebriel AU - Komi Mensah Agboka Y1 - 2024/12/31 PY - 2024 N1 - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13 DO - 10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13 T2 - American Journal of Remote Sensing JF - American Journal of Remote Sensing JO - American Journal of Remote Sensing SP - 53 EP - 70 PB - Science Publishing Group SN - 2328-580X UR - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajrs.20241202.13 AB - Drought is one of the most frequent natural disasters in the world, droughts has a significantly negative impact on social, economic, and environmental situations. The goal is to assess and define the spatiotemporal analysis of meteorological droughts across ENSO (neutral, El Niño and La Niña) events and provided the guidance of the study area. CHIRPS data gathered from CHG-UCSB for spatial analysis and USGS FEWS NET for temporal analysis, respectively, for the time periods 1981 2020 and 1991–2020. For spatial and temporal analysis SPI was selected due to better for rainfall input over the study area, we employed Python tools and GeoCLIM data analysis methodologies. The findings of this study demonstrate that the Borana zone experienced an increase in droughts during the El Niño, La Niña, and neutral events between 1981 and 2020. The frequency and duration of the dryness were displayed in time steps across short-term drought indices. The extent, duration, and frequency of meteorological (deficit of precipitation) droughts varied, as shown by the time-scale temporal meteorological drought indices in the range of three to twelve months. For the remaining woredas of investigation between the SPI3 and SPI6, SPI6 and SPI12, and SPI9 and SPI12 indices, significantly an increase in the correlation values over short to long durations over the study area was the dominant factor in the meteorological drought severity of the correlation. It is also necessary to conduct additional research on how droughts spread, including the use of various drought indices to gauge the frequency, length, and intensity of droughts over time at the woreda, regional, and national levels. This study will help for different sectors, for knowledge’s and references to better manage irrigation, crop variety selection (drought tolerant seeds), soil conservation, crop production, and better awareness on meteorological droughts over study area. VL - 12 IS - 2 ER -