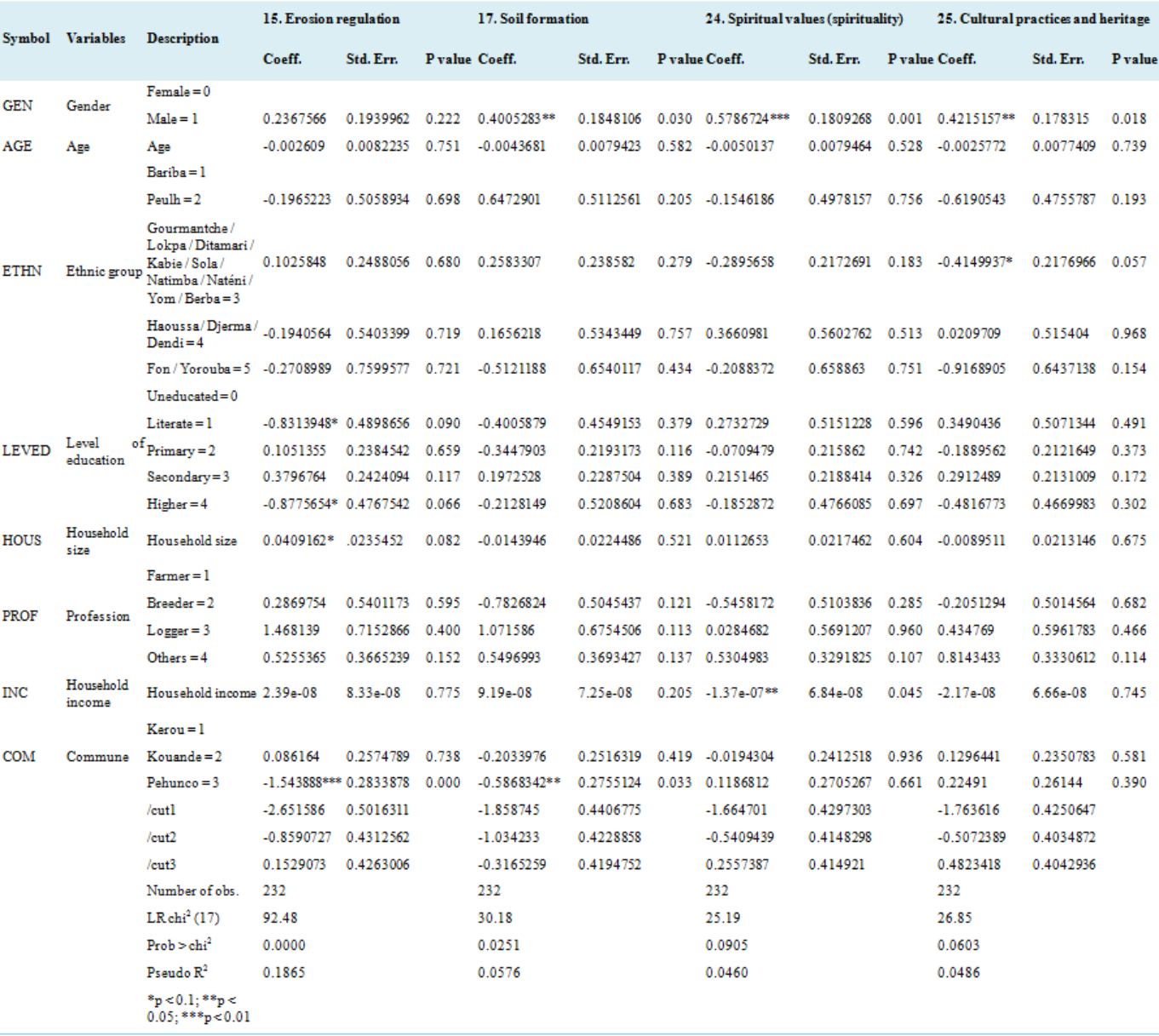

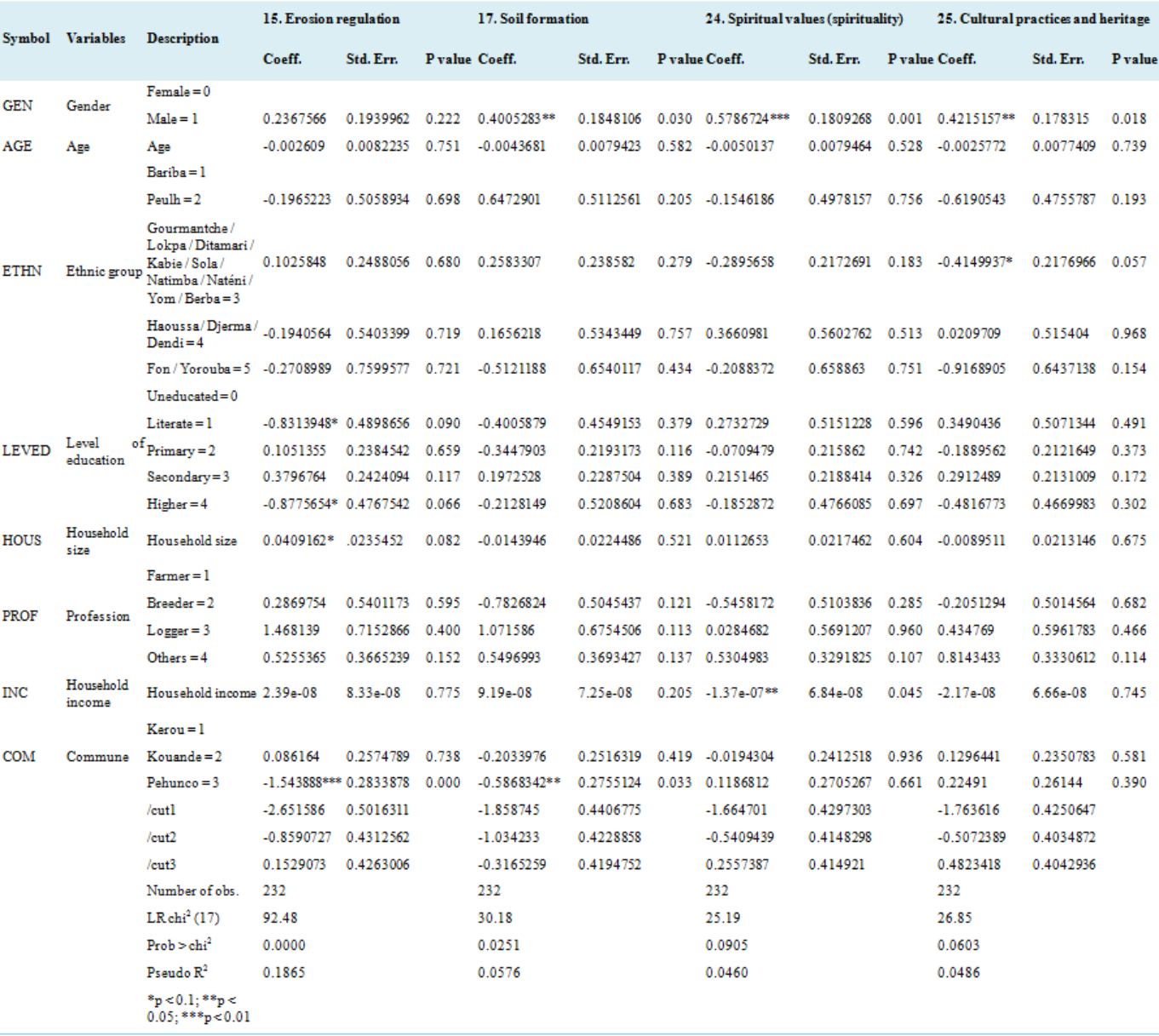

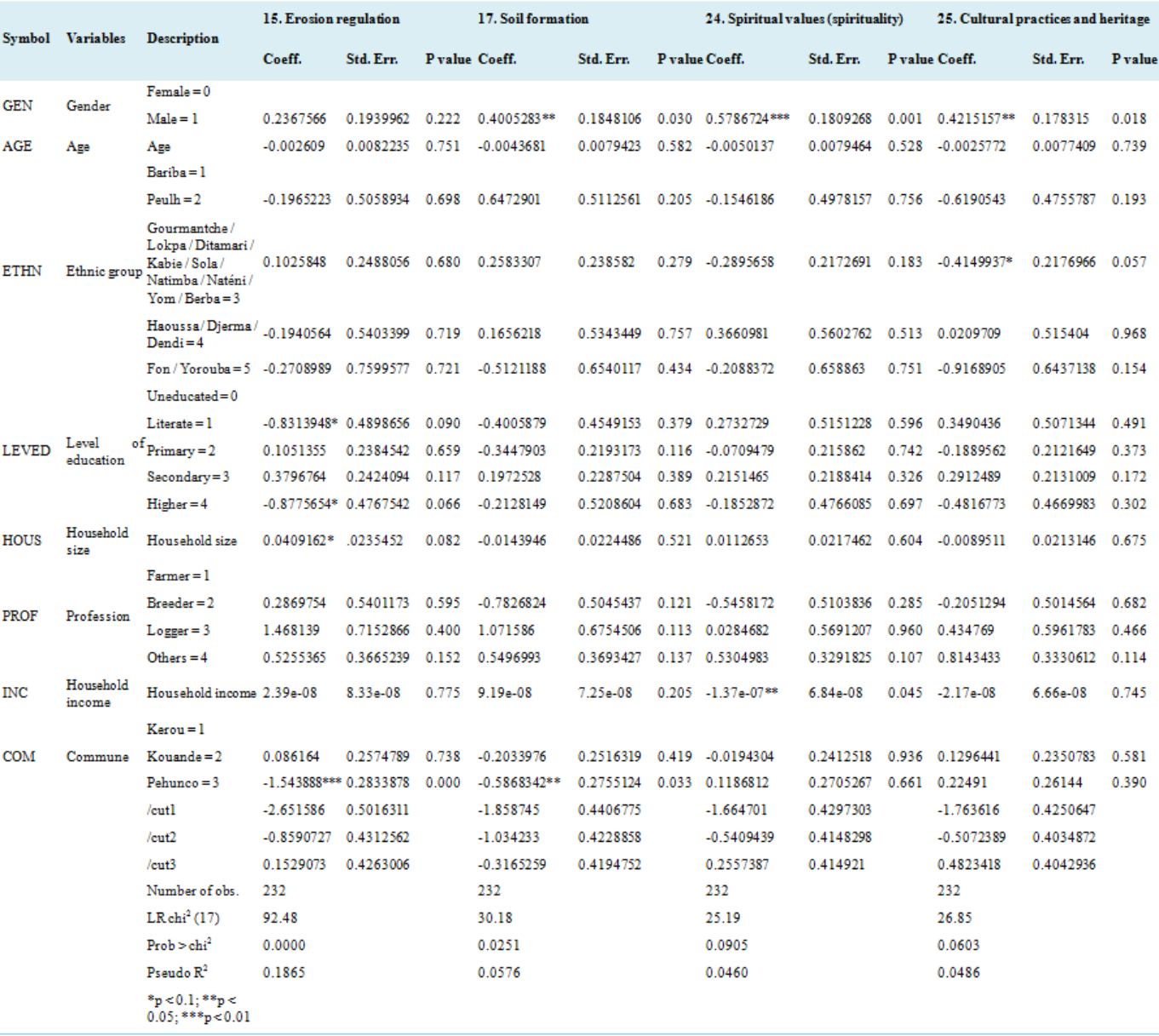

Ecosystem services are closely linked to the daily lives of local communities, particularly those living near forests. The study of the local perceptions of these services is relevant because they vary depending on the community, the study period, and the environment. So beyond the inventorying of ecosystem services, understanding the perceptions of local communities regarding these services remains a necessity. Our study aims to analyze how local communities perceive the ecosystem services provided by forests and the factors that determine these perceptions. We collected data from 232 heads of households across 23 villages bordering the forest and analyzed them using descriptive statistics and ordered Probit analysis. The results showed that provisioning services (such as plant-derived medicines, rafters and planks, livestock feed, crops, and firewood) were the most important, followed by regulating and supporting services (including soil formation, erosion control, and climate regulation) are the most important. Finally, cultural services (encompassing cultural practices, heritage, and spirituality) were perceived as important. However, communities did not perceive the value of ecotourism. Factors influencing these perceptions included gender (male), age (young individuals), occupation in farming, household size, level of education, Bariba ethnicity and income. To ensure the sustainable utilization of forest resources in the region, it is necessary to encourage young people to adopt environmentally friendly agricultural practices, to use improved stoves that require less wood and promote cultural services to diversify their sources of income.

| Published in | American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry (Volume 12, Issue 2) |

| DOI | 10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16 |

| Page(s) | 113-128 |

| Creative Commons |

This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. |

| Copyright |

Copyright © The Author(s), 2024. Published by Science Publishing Group |

Benin, Ecosystem Services, Forest, Local Communities, Local Perceptions, Natural Resource Use

Variables | Symbols | Comments | Variable type |

|---|---|---|---|

Gender | GEN | Gender (Female = 0; Male = 1) | Nominal |

Age | AGE | Respondent's age | Quantitative |

Ethnicity | ETHN | Ethnicity or mother tongue of individuals (Bariba = 1; Peulh = 2; Gourmantche / Lokpa / Ditamari / Kabie / Sola / Natimba / Naténi / Yom / Berba = 3; Haoussa / Djerma / Dendi = 4; Fon / Yorouba = 5) | Ordinal |

Level of education | LEVED | Respondents' level of education (0 = Uneducated; 1 = Literate; 2 = Primary; 3 = Secondary; 4 = Higher) | Ordinal |

Household size | HOUS | Size of household headed by the respondent | Quantitative |

Profession | PROF | Profession of head of the household surveyed (1 = Farmer; 2 = Breeder; 3 = Logger; 4 = Other) | Ordinal |

Income | INC | Household income according to respondent | Quantitative |

Commune | COM | Commune of respondent (1 = Kerou; 2 = Kouande; 3 = Pehunco) | Ordinal |

Symbols | Variables | Description | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

GEN | Gender | Male | 162 | 69.83 |

Female | 70 | 30.17 | ||

ETHN | Ethnic group or mother tongue | Bariba | 170 | 73.28 |

Peulh | 10 | 4.31 | ||

Gourmantche / Lokpa / Ditamari / Kabie / Sola / Natimba / Naténi / Yom / Berba | 44 | 18.97 | ||

Haoussa / Djerma / Dendi | 5 | 2.16 | ||

Fon / Yorouba | 3 | 1.29 | ||

LEVED | Level of education | Uneducated | 142 | 61.21 |

Literate | 6 | 2.59 | ||

Primary | 36 | 15.52 | ||

Secondary | 42 | 18.10 | ||

Higher | 6 | 2.59 | ||

PROF | Profession | Farmer | 204 | 87.93 |

Breeder | 9 | 3.88 | ||

Logger | 4 | 1.72 | ||

Others | 15 | 6.47 | ||

COM | Individual's commune | Kerou | 31 | 13.36 |

Kouande | 141 | 60.78 | ||

Pehunco | 60 | 25.86 |

Variables | Mean | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

AGE | 47.21 | 20 | 80 |

HOUS | 9.02 | 0 | 30 |

INC | 870,388 | 45,000 | 10,000,000 |

| [1] | Westman, W. E. How much are nature’s services worth?, Science, 1977, 197(4307), 960-964. |

| [2] | Ehrlich, P. R., Mooney, H. A. Extinction, Substitution, and Ecosystem Services. BioScience. 1983, 33(4), 248-254. |

| [3] | Costanza, R. et al. The Value of the World’s Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital. 1997, 387(6630), 253-260. |

| [4] | Danley, B., Widmark, C. Evaluating conceptual definitions of ecosystem services and their implications. Ecological Economic. 2016, 126, 132-138. |

| [5] | de Groot, R. S., Wilson, M. A., Boumans, R. M. J. A typology for the classification, description and valuation of ecosystem functions, goods and services. Ecological Economics. 2002, 41(3), 393-408. |

| [6] | Millennium, E. A. Ecosystems and human well-being: wetlands and water synthesis: a report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2005. |

| [7] | de Groot, R. S., Alkemade, R., Braat, L., Hein, L., Willemen, L. Challenges in integrating the concept of ecosystem services and values in landscape planning, management and decision making. Ecological Complexity. 2010, 7(3), 260-272. |

| [8] | Gouwakinnou, G. N., Biaou, S., Vodouhe, F. G., Tovihessi, M. S., Awessou, B. K., Biaou, H. S. S. Local perceptions and factors determining ecosystem services identification around two forest reserves in Northern Benin. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine. 2019, 15(1), 61. |

| [9] | Sunderlin, W. D. et al., Livelihoods, forests, and conservation in developing countries: An Overview. World Development. 2005, 33(9), 1383-1402. |

| [10] | Cámara-Leret, R., Fortuna, M. A., Bascompte, J. Indigenous knowledge networks in the face of global change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116(20), 9913-9918. |

| [11] | Gaoue, O. G., Ticktin, T. Patterns of harvesting foliage and bark from the multipurpose tree Khaya senegalensis in Benin: Variation across ecological regions and its impacts on population structure. BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION. 2007, 137(3), 424-436. |

| [12] | Fandohan, B., Glele, K. R., Sinsin, B., Pelz, D. CARACTERISATION DENDROMETRIQUE ET SPATIALE DE TROIS ESSENCES LIGNEUSES MEDICINALES DANS LA FORET CLASSEE DE WARI-MARO AU BENIN. 2008, 12, 173-186. |

| [13] | Sambou, A., Camara, B., Kémo, A. O., Coly, A. Badji, A. Perception des populations locales sur les services écosystèmiques de la forêt classée et aménagée de Kalounayes (Sénégal). 2018, 19. |

| [14] | Vodouhê, G. F., Coulibaly, O., Sinsin, B. Estimating local values of vegetable non-timber forest products to Pendjari Biosphere Reserve dwellers in Benin. IUFRO World Series. 2009, 23(63-72). |

| [15] | Angelsen, A. et al. Environmental Income and Rural Livelihoods: A Global-Comparative Analysis », World Development. 2014, 64, S12-S28. |

| [16] | Ickowitz, A., Powell, B., Salim, M. A., Sunderland, T. C. H. Dietary quality and tree cover in Africa. Global Environmental Change. 2014, 24, 287-294. |

| [17] | FAO, PNUE. La situation des forêts du monde 2020. Forêts, biodiversité et activité humaine. Rome. 2020. |

| [18] | Lhoest, S., Dufrêne, M., Vermeulen, C., Oszwald, J., Doucet, J.-L., Fayolle, A. Perceptions of ecosystem services provided by tropical forests to local populations in Cameroon. Ecosystem Service. 2019, 38, 100956. |

| [19] | Clark, D. A. Sources or sinks? The responses of tropical forests to current and future climate and atmospheric composition », Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2004, 359(1443), 477-491. |

| [20] | Lewis, S. L. et al. Increasing carbon storage in intact African tropical forests. Nature. 2009,457(7232), 1003-1006. |

| [21] | Sloan, S., Sayer, J. A. Forest Resources Assessment of 2015 shows positive global trends but forest loss and degradation persist in poor tropical countries., Forest Ecology and Management. 2015, 352, 134-145. |

| [22] | Adjonou, K., Ali, N., Kokutse, A. D., Novigno, S. K. Etude de la dynamique des peuplements naturels de Pterocarpus ericaceus Poir.(Fabaceae) surexploités au Togo. Bois & Forêts des Tropiques. 2010, 306, 45-55. |

| [23] | Vodouhê, F. G., Coulibaly, O., Adégbidi, A., Sinsin, B. Community perception of biodiversity conservation within protected areas in Benin. Forest Policy and Economics. 2010, 12(7), 505-512. |

| [24] | Collins S. L., et al. An integrated conceptual framework for long‐term social–ecological research. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2011, 9(6), 351-357. |

| [25] | Sodhi, N. S. et al. Local people value environmental services provided by forested parks. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2010, 19(4), 1175-1188. |

| [26] | Djossa, B. A., Toni, H., Dossa, K., Azonanhoun, P., Sinsin, B. Local perception of ecosystem services provided by bats and bees and their conservation in Bénin, West Africa. International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences. 2012, 6(5), 2034-2042. |

| [27] | Asah, S. T., Guerry, A. D., Blahna, D. J., Lawler, J. J. Perception, acquisition and use of ecosystem services: Human behavior, and ecosystem management and policy implications. Ecosystem Services. 2014, 10, 180-186. |

| [28] | Castro, A. J., Martín-López, B., García-Llorente, M., Aguilera, P. A., López, E., Cabello, J. Social preferences regarding the delivery of ecosystem services in a semiarid Mediterranean region. Journal of Arid Environments. 2011, 75(11), 1201-1208. |

| [29] | de Freitas, C. T., Shepard Jr, G. H., Piedade, M. T. The floating forest: traditional knowledge and use of matupá vegetation islands by riverine peoples of the Central Amazon. PloS one. 2015, 10(4), e0122542. |

| [30] | Boafo, Y. A., Saito, O., Kato, S., Kamiyama, C., Takeuchi, K., Nakahara, M. The role of traditional ecological knowledge in ecosystem services management: the case of four rural communities in Northern Ghana. International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management. 2016, 12(1-2), 24-38. |

| [31] | Houde, N. The six faces of traditional ecological knowledge: challenges and opportunities for Canadian co-management arrangements. Ecology and Society. 2007, 12(2). |

| [32] | LaRochelle, S., Berkes, F. Traditional ecological knowledge and practice for edible wild plants: Biodiversity use by the Rarámuri, in the Sirerra Tarahumara, Mexico. The International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. 2003, 10(4), 361-375. |

| [33] | Parrotta, J. A., Agnoletti, M. Traditional forest-related knowledge and climate change. in Traditional Forest-Related Knowledge, Springer. 2012, 491-533. |

| [34] | Braat, L. C., De Groot, R. The ecosystem services agenda: bridging the worlds of natural science and economics, conservation and development, and public and private policy, Ecosystem services,. 2012, 1(1), 4-15. |

| [35] | Parrotta, J., Yeo-Chang, Y., Camacho, L. D. Traditional knowledge for sustainable forest management and provision of ecosystem services. 2016. |

| [36] | Martín-López, B., et al. « Uncovering ecosystem service bundles through social preferences. PLoS one. 2012, 7(6), e38970. |

| [37] | Keune, H., et al. Emerging ecosystem services governance issues in the Belgium ecosystem services community of practice. Ecosystem services. 2015,16, 212-219. |

| [38] | Kremen, C., Ostfeld, R. S. A. call to ecologists: measuring, analyzing, and managing ecosystem services. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2005, 3(10), 540-548. |

| [39] | Satz, D., et al. The challenges of incorporating cultural ecosystem services into environmental assessment. Ambio. 2013, 42(6), 675-684. |

| [40] | Cuni-Sanchez, A., Pfeifer, M., Marchant, R., Burgess, N. D. Ethnic and locational differences in ecosystem service values: Insights from the communities in forest islands in the desert. Ecosystem Services. 2016, 19, 42-50. |

| [41] | Zhang, W., et al. Awareness and perceptions of ecosystem services in relation to land use types: Evidence from rural communities in Nigeria. Ecosystem Services. 2016, 22, 150-160. |

| [42] |

INSAE, RGPH-4. PRINCIPAUX INDICATEURS SOCIO DEMOGRAPHIQUES ET ECONOMIQUES (RGPH4-2013). Available from:

https://www.google.com/search?source=hp&ei=bzFgXLXaJKivgwfF1ZTAAw&q=RGPH4+ (Assessed 10 february 2019) |

| [43] | Dave, R., Tompkins, E. L., Schreckenberg, K. Forest ecosystem services derived by smallholder farmers in northwestern Madagascar: Storm hazard mitigation and participation in forest management. Forest Policy and Economics. 2017,84, 72-82. |

| [44] | Gillingham, S., Lee, P. C. The impact of wildlife-related benefits on the conservation attitudes of local people around the Selous Game Reserve, Tanzania. Environmental Conservation. 1999, 218-228. |

| [45] | Mehta, J. N., Heinen, J. T. Does community-based conservation shape favorable attitudes among locals? An empirical study from Nepal. Environmental management. 2001, 28(2), 165-177. |

| [46] | Ouko, C. A., Mulwa, R., Kibugi, R., Owuor, M. A., Zaehringer, J. G., Oguge, N. O. Community perceptions of ecosystem services and the management of Mt. Marsabit Forest in Northern Kenya., Environments. 2018, 5(11), 121. |

| [47] | Moutouama, F. T., Biaou, S. S. H., Kyereh, B., Asante, W. A., Natta, A. K. Factors shaping local people’s perception of ecosystem services in the Atacora Chain of Mountains, a biodiversity hotspot in northern Benin. Journal of ethnobiology and ethnomedicine. 2019, 15(1) 1-10. |

| [48] | Kinzer, A. Zones of Influence: Forest Resource Use, Proximity, and Livelihoods in the Kijabe Forest. 2018. |

| [49] | Muhamad, D., Okubo, S., Harashina, K., Parikesit, Gunawan, B., Takeuchi, K. Living close to forests enhances people׳s perception of ecosystem services in a forest–agricultural landscape of West Java, Indonesia. Ecosystem Services. 2014, 8, 197-206. |

| [50] | Hartel, T., Fischer, J., Câmpeanu, C., Milcu, A. I., Hanspach, J., Fazey, I. The importance of ecosystem services for rural inhabitants in a changing cultural landscape in Romania. E&S. 2014, 19, 2, art42, 2014, |

| [51] | Mensah, S. SELECTED KEY ECOSYSTEM SERVICES, FUNCTIONS, AND THE RELATIONSHIP WITH BIODIVERSITY IN NATURAL FOREST ECOSYSTEMS. Doctoral dissertation, Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, 2016. |

| [52] |

FAO. La situation mondiale de l’alimentation et de l’agriculture 2005. Available from:

http://www.fao.org/docrep/008/a0050f/a0050f19.htm (Assessed 10 février 2022) |

| [53] | Ryan, C. M., Pritchard, R., McNicol, I., Owen, M., Fisher, J. A., Lehmann, C. Ecosystem services from southern African woodlands and their future under global change. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B.2016, 371(1703), 20150312. |

| [54] | Hountondji, Gaoué, O. G., Sokpon, N., Ozer, P. Analyse écogéographique de la fragmentation du couvert végétal au nord Bénin : paramètres dendrométriques et phytoécologiques comme indicateurs in situ de la dégradation des peuplements ligneux. Geo-Eco-Trop: Revue Internationale de Géologie, de Géographie et d’Écologie Tropicales. 2013, 37(1). |

| [55] | Hartter, J. Resource Use and Ecosystem Services in a Forest Park Landscape. Society & Natural Resources. 2010, 23(3), 207-223. |

| [56] | Warren-Rhodes, K. et al. Mangrove ecosystem services and the potential for carbon revenue programmes in Solomon Islands. Envir. Conserv. 2011, 38(4,), 485-496. |

| [57] | Allendorf, T. D., Yang, J. The role of ecosystem services in park–people relationships: The case of Gaoligongshan Nature Reserve in southwest China. Biological Conservation. 2013, 167, 187-193. |

| [58] | Poppenborg, P. Koellner, T. Do attitudes toward ecosystem services determine agricultural land use practices? An analysis of farmers’ decision-making in a South Korean watershed. Land Use Policy. 2013, 31, 422-429. |

APA Style

Sourokou, R., Vodouhe, F. G. (2024). Local Perceptions of Forest-Based Ecosystem Services in Benin, West Africa. American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 12(2), 113-128. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16

ACS Style

Sourokou, R.; Vodouhe, F. G. Local Perceptions of Forest-Based Ecosystem Services in Benin, West Africa. Am. J. Agric. For. 2024, 12(2), 113-128. doi: 10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16

AMA Style

Sourokou R, Vodouhe FG. Local Perceptions of Forest-Based Ecosystem Services in Benin, West Africa. Am J Agric For. 2024;12(2):113-128. doi: 10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16

@article{10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16,

author = {Robert Sourokou and Fifanou Gbèlidji Vodouhe},

title = {Local Perceptions of Forest-Based Ecosystem Services in Benin, West Africa

},

journal = {American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry},

volume = {12},

number = {2},

pages = {113-128},

doi = {10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16},

url = {https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16},

eprint = {https://article.sciencepublishinggroup.com/pdf/10.11648.j.ajaf.20241202.16},

abstract = {Ecosystem services are closely linked to the daily lives of local communities, particularly those living near forests. The study of the local perceptions of these services is relevant because they vary depending on the community, the study period, and the environment. So beyond the inventorying of ecosystem services, understanding the perceptions of local communities regarding these services remains a necessity. Our study aims to analyze how local communities perceive the ecosystem services provided by forests and the factors that determine these perceptions. We collected data from 232 heads of households across 23 villages bordering the forest and analyzed them using descriptive statistics and ordered Probit analysis. The results showed that provisioning services (such as plant-derived medicines, rafters and planks, livestock feed, crops, and firewood) were the most important, followed by regulating and supporting services (including soil formation, erosion control, and climate regulation) are the most important. Finally, cultural services (encompassing cultural practices, heritage, and spirituality) were perceived as important. However, communities did not perceive the value of ecotourism. Factors influencing these perceptions included gender (male), age (young individuals), occupation in farming, household size, level of education, Bariba ethnicity and income. To ensure the sustainable utilization of forest resources in the region, it is necessary to encourage young people to adopt environmentally friendly agricultural practices, to use improved stoves that require less wood and promote cultural services to diversify their sources of income.

},

year = {2024}

}

TY - JOUR T1 - Local Perceptions of Forest-Based Ecosystem Services in Benin, West Africa AU - Robert Sourokou AU - Fifanou Gbèlidji Vodouhe Y1 - 2024/04/29 PY - 2024 N1 - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16 DO - 10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16 T2 - American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry JF - American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry JO - American Journal of Agriculture and Forestry SP - 113 EP - 128 PB - Science Publishing Group SN - 2330-8591 UR - https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajaf.20241202.16 AB - Ecosystem services are closely linked to the daily lives of local communities, particularly those living near forests. The study of the local perceptions of these services is relevant because they vary depending on the community, the study period, and the environment. So beyond the inventorying of ecosystem services, understanding the perceptions of local communities regarding these services remains a necessity. Our study aims to analyze how local communities perceive the ecosystem services provided by forests and the factors that determine these perceptions. We collected data from 232 heads of households across 23 villages bordering the forest and analyzed them using descriptive statistics and ordered Probit analysis. The results showed that provisioning services (such as plant-derived medicines, rafters and planks, livestock feed, crops, and firewood) were the most important, followed by regulating and supporting services (including soil formation, erosion control, and climate regulation) are the most important. Finally, cultural services (encompassing cultural practices, heritage, and spirituality) were perceived as important. However, communities did not perceive the value of ecotourism. Factors influencing these perceptions included gender (male), age (young individuals), occupation in farming, household size, level of education, Bariba ethnicity and income. To ensure the sustainable utilization of forest resources in the region, it is necessary to encourage young people to adopt environmentally friendly agricultural practices, to use improved stoves that require less wood and promote cultural services to diversify their sources of income. VL - 12 IS - 2 ER -